Good morning, subscriber!

And welcome to the end of another week. I hope spring is springing wherever you may be! As usual this time of year, I’m spending my free time searching for winged migrants gracious enough to bless me with their feathery presence.

Speaking of the heavens, today I’d like to chat about Christianity; in particular, evangelicalism. In a recent article in the Times, reporters Elizabeth Dias and Ruth Graham examined how evangelical worship became a staple of right-wing protests during the pandemic. Now, they write, “many believers are importing their worship of God, with all its intensity, emotion and ambitions, to their political life.” Unsurprisingly, this worship often takes an orange hue. “Father in heaven, we firmly believe that Donald Trump is the current and true president,” proclaimed one preacher at a rally in Michigan.

Though illuminating, I have a few bones to pick with this article. First, there’s barely any mention of race, which is significant because evangelicals praying to the big sparrow in the sky sure seem to have one dominant physical trait in common:

Second, and related, there’s barely any historical context beyond mentioning that “the Christian right has been intertwined with American conservatism for decades, culminating in the Trump era.” This tidy summation of over a hundred years of history obscures one or two points, including the nasty fact that contemporary evangelical ideology is rooted in antebellum definitions of masculinity. Indeed, as historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez argues, the Trump era was not merely the culmination of the Christian right’s embrace of conservatism but rather “the culmination of evangelicals’ embrace of militant masculinity” over the last 120 years.1

And to see why this is a telling, foreboding distinction to make, let’s talk about some self-conscious men.

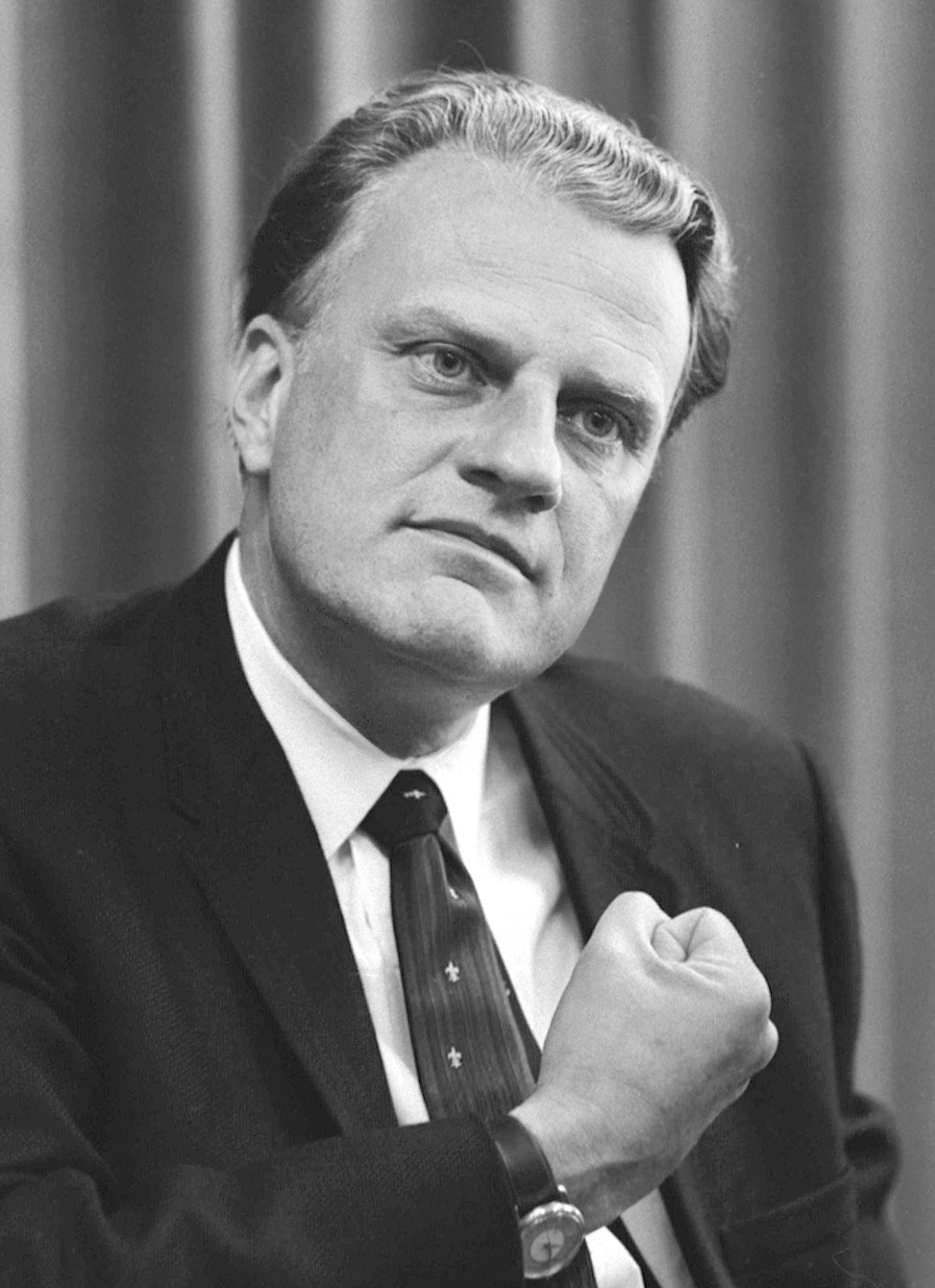

In the early 1900s, as more and more US citizens moved to cities, Protestant men suffered a bit of a mass identity crisis. In the old days of growing taters on the farm, “Christian manhood entailed hard work and thrift,” writes Du Mez.2 But as the hardworking fellas switched to working on assembly lines, their once-lionized piety and strength weren’t as useful. Lest they grow soft and become associated with “womanly virtues,” in the 1910s, white native-born Protestant men set out to “re-masculinize” American Christianity.3 Led by figures like Billy Sunday, a baseball player turned evangelical minister, they began to identify as “essentially masculine, militant, warlike.” Sunday was known to pack his “old muzzle-loading Gospel gun” with “buttermilk, rough on rats, rock salt, and whatever else came in handy.”4 Conveniently, this description doubled as his use-what-you-have-in-your-pantry pancake recipe 😋.

Less conveniently, his definition of “Christian manhood” was at odds with Christian morality, and it surely presented a problem for evangelicals, who defined themselves in part by spreading the word of the Bible, privileging humility, and elevating “the least” of society. Yet as Du Mez notes, there was precedent for “tinkering with Christian virtue.” In the 1700s, southern evangelicals devised the notion that “to maintain order and fulfill their role as protectors, there were times when Christian men must resort to violence.”5 In reality, this was a white supremacist justification for hierarchical control over women, children, Native Americans, and enslaved Africans, but that didn’t disturb Sunday, who revived “muscular Christianity” with distasteful zeal. When World War I rolled around, he added a nationalist flavor to his faith, criticizing pacifists and draft dodgers, and maintaining that “in these days all are patriots or traitors, to your country and the cause of Jesus Christ.”6

Unfortunately for evangelicals, this new articulation of Christian masculinity didn’t jive so well with the war’s vicious reality. “When the war came to a close,” reviews Du Mez, no amount of Sunday-esque patriotism “could obscure the fact that it had been fought at great cost, and with little apparent gain.” So, evangelicals toned down their belligerent rhetoric and in the US’ fast-growing industrial economy, began to associate religion more with running an efficient business. For example, in 1925, Bruce Barton, an advertising executive, depicted Jesus as a “winner” and “the world’s greatest business executive,”7 at long last helping to explain this early draft of The Last Supper:

Despite attempts to revamp Jesus’ image, the evangelical population remained relatively small. As late as 1942, only around two million people in the US, or around 2% of the population, identified as evangelical. That year, at the first meeting of the National Association of Evangelicals, Reverend Harold John Ockenga conceded that evangelicalism had for decades “suffered nothing but a series of defeats,” and “a new era in evangelical Christianity” was needed.8 Billy Graham soon answered his prayers—by going back to an older era.