Good morning, subscriber!

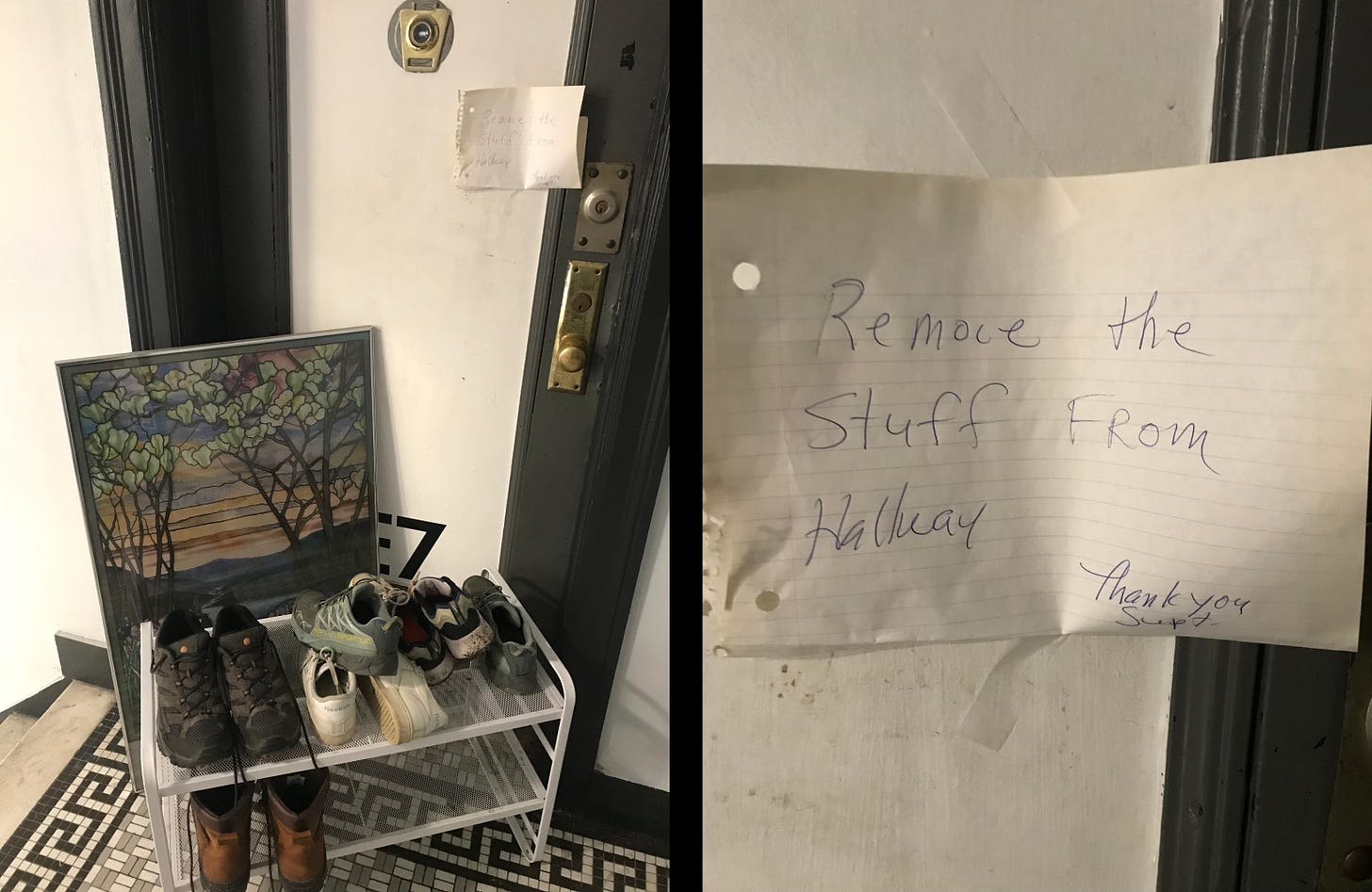

And congrats on making it to the end of another week. I’d say the gods are testing us these days, but that’d be giving a little too much credit to the Supreme Court, and to my building’s superintendent, who took the liberty of rearranging my things while I was out birding one day:

Last week’s news was a doozy. If/when Roe is overturned, roughly half of US states, largely in the South and Midwest, are expected to ban abortion. Black and Hispanic women, who receive disproportionate numbers of abortions in those states, will bear the brunt of this change.

According to the AP, “these women—often poor—will likely have the hardest time traveling to distant parts of the country to terminate pregnancies or raising children they might struggle to afford.” Unmentioned in this important point? Why women and members of communities of color are “often poor.” Much like my super’s curiously artful presentation of hiking shoes, I don’t take this point for granted.

Which is why today I’d like to focus on a related topic that’s gone particularly under the radar: the built-in inequities of Black banking. Thanks to segregation, for almost a hundred years, Black banks have been unable to generate money for the minority communities they serve. The result is the entrenchment of the wealth gap that SCOTUS’ repugnant shenanigans bring into stark contrast today.

To see what I mean, let’s talk about crossbreeds at the end of the Civil War.

In 1865, Abraham Lincoln signed the Freedmen’s Bureau Act, which set aside 400,000 acres of confiscated land for freed people. Agents of the newly established Freedmen’s Bureau began promising mules to go along with 40 acres of land for each freed person, presumably knowing that nothing sweetens a deal like a cross between a horse and a donkey—except, of course, for a cross between a dog and a dolphin:

The Black community welcomed the (paltry) reparations for hundreds of years of enslavement. Predictably, white southerners were less enthusiastic. As historian Mehrsa Baradaran writes, “confiscating and breaking up the land meant destroying the slaveholder oligarchies that had controlled the Confederacy.” After Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson became president, he abetted ex-Confederates’ attempts to restore a “white man’s government.” One way he did this? By rolling back Lincoln’s land grant and telling Black people that if they wanted to “establish for themselves a condition of respectability and prosperity,” they should put their money in a bank.1

Specifically, he meant the Freedmen’s Savings Bank, which Congress established at the same time as the Freedmen’s Bureau. Pamphlets promoted the bank as “Abraham Lincoln’s Gift to the Colored People,” and with few other options, freed people’s response to the bank was remarkable. Within ten years, it handled more than $75 million of deposits, or around $1.5 billion today, made by more than 75,000 depositors.2

But there was a catch. In 1867, a journalist named Henry Cooke took over the bank’s finances.