Good morning, subscriber!

And welcome to the end of another week. As I write to you, I’m seated in front of a eucalyptus tree in northern Portugal (not an April Fool’s joke!). I hope the world is smelling good from your vantage point, too.

Something undeniably putrid? Republican-controlled legislatures’ recent spate of attacks on the LGBTQ community. Many states, including Florida, Idaho, and Texas, have banned gender-affirming healthcare for transgender children. Meanwhile, on Monday, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law the Parental Rights in Education bill, aka the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. The law dictates that classroom instruction on “sexual orientation or gender orientation may not occur in kindergarten through grade three.” Mega sigh. If all it took to eradicate an identity was not saying it aloud, I wouldn’t be in a Portuguese park but rather on the streets advocating for laws that banned the words “conservative,” “Republican,” and “talkative dentist.”

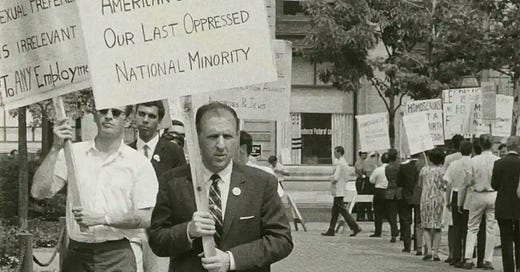

Alas, absurd (not to mention vile and destructive) has defined US policies toward the LGBTQ community over much of the last 100 years. An illuminating illustration of the government’s ludicrous stance toward people termed “sexual deviants” occurred in the 1950s, when many federal employees lost their jobs simply because of their sexual orientation. An astronomer named Frank Kameny decided to fight back, and his story not only reveals the origins of the idea of gay pride but how far the US has and hasn’t come in supporting the LGBTQ community.

To see how, let’s first talk about a double agent in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

With slightly graying blond hair and a “greasy” outward appearance, Alfred Redl was a formidable, kind-of-silver-foxy colonel in the Austrian military. In the early 1900s, he almost single-handedly built the empire’s counter-espionage program, gaining more access to classified information than “perhaps anyone else in the empire,” writes historian Eric Cervini.1 Redl was also openly gay and appeared at society events with his longtime “nephew,” while maintaining several other affairs. Unbeknownst to Austrians, however, the lavish gifts he gave his lovers came courtesy of the cash he earned by selling Austrian war plans to Italy and Russia.

Redl’s fun little scheme came crashing down in May 1913 when Austrian officials intercepted a Russian letter containing six thousand krone. The timing wasn’t ideal. World War I started the following year, and by the end of 1914, Austria had suffered more than a million casualties. When news of Redl’s treason leaked, Austrian officials decided to scapegoat Redl, as well as a nonexistent “homosexual organization” within the military, for the country’s staggering wartime losses. As this rumor spread, “the myth of the homosexual traitor came into being,” asserts Cervini.2

Why start with this tale? Well, loath to miss out on a damaging stereotype, a coalition of US politicians began peddling the same fallacy after World War II. Intent on diminishing the power of liberal Democrats like FDR and later Harry Truman, Republicans and southern Democrats exploited the uncertainty of the new world order by spreading rumors of traitors within the US government. Famously, their efforts to “ferret out” threats to the “American way of life” led to Senator Joe McCarthy’s hunt for mythical Communist government employees, as well as the shocking discovery of lots of very cute little furry animals who’d secretly commandeered the US’ wartime efforts.

Less famously, McCarthy and co also targeted the LGBTQ community, in what became known as the Lavender Scare. In 1950, a Senate committee held closed hearings in 1950 to “determine the extent of the employment of homosexuals and other sex perverts in Government.” The committee’s star witness was Admiral Roscoe Hillenkoeter, director of the newly created CIA, who arrived at the hearing with a 38-page statement detailing the ipso facto security risks that homosexuals presented. His evidence? The “classic” case “known all through intelligence circles” of Alfred Redl, whose tale supposedly proved the government “should not employ homosexuals or other moral perverts in positions of power.” Relying on this urban legend, Hillenkoiter’s testimony “became the primary piece of evidence that guided federal employment policy toward homosexuals for decades to come,” notes Cervini.3

This was bad news for anyone who believed in morality and logic, as well as for government employees like Frank Kameny.