Good morning, subscriber!

Well, as the world goes down in flames, it seems even cats are growing upset. On Monday (July 4th), my family’s black kitty disappeared for 20 hours. He eventually emerged, a little ragged but fine, and though it seems like he got in a scrap with a raccoon, I’m pretty sure he was protesting the Supreme Court—and then got in a scrap with a raccoon.

I understand his frustration. SCOTUS’ new right-wing supermajority eradicated the executive branch’s chance to fight climate change, eroded tribal sovereignty, decimated Roe v. Wade, and a whole lot more. In short, it was conservative Christmas. Nikole Hannah Jones added some ominous historical perspective:

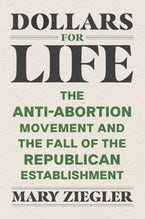

Amid the near-blinding totality of this bleakness, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that the GOP wasn’t always gung-ho about removing corporate restrictions and a woman’s right to choose. The roots of a surprising, overlooked alliance between anti-abortion activists and corporate titans date back to the late 70s. Together, they’ve used the unelected power of the Supreme Court to implement agendas that, enragingly, undermine popular sentiment.

To see how, let’s begin in early 1973.

Less than a month after Roe v. Wade, the leaders of anti-abortion organizations, religious conservatives, and other major pro-life groups gathered in DC. Their focus? To figure out the next steps in subverting women’s rights (I’m summarizing). They agreed to push for a constitutional amendment that either granted citizens legal protection from the moment of conception or defined the word “person” in the Constitution as “all human beings, including their unborn offspring.” And the key, they thought, to proving that every sperm deserved its own bill of rights, was public education. Historian Mary Ziegler describes how Catholic activists John and Barbara Willke, who’d toured the country giving slideshows showing what “real abortions” looked like, inspired the assembled anti-abortion movement. The pro-lifers reasoned that “if the national media carried something similar” to the Willkes’ slideshows, then “voters (and therefore politicians) would take their side.”1

Not so fast. Though organizations like the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) launched national newsletters, and a pro-life media ecosystem formed, the propaganda didn’t end up swaying politicians. Neither Gerald Ford, the Republican nominee for president in 1976, nor Jimmy Carter, the Democratic nominee, would commit to an amendment banning abortions. Further, the Senate tabled a Human Life Amendment (HLA) proposed by North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, a segregationist who described Civil Rights activists as “moral degenerates.”2 His lack of success led James Bopp, a prominent anti-abortion lawyer, to begin pursuing alternate strategies.

Raised in Indiana, James’ mom was a homemaker who co-hosted talks about the threat of socialism, and his father, a doctor, believed that abortion violated the Hippocratic Oath. Inspired by the hosts of the world’s worst dinner parties, as well as his mentor and conservative commentator Stan Evans, James became a lawyer hellbent on reversing Roe v. Wade. In the mid-70s, he joined with other attorneys in writing restrictive abortion laws. For example, he drafted a model law passed in Florida that required abortion clinics to meet burdensome standards that made them likelier to close. Bopp, who would soon become General Counsel for the NRLC, also assisted like-closeminded lawyers in abortion cases that followed Roe. In one case, SCOTUS upheld a Missouri informed consent requirement, allowing pro-life staff at clinics to distribute misleading information. Other cases led to SCOTUS upholding the Hyde Amendment, which banned Medicaid reimbursement for abortion. With over 50% of the country believing that abortion should be legal, the pro-life outcomes convinced Bopp that “the Supreme Court held out more promise” than popular support for a constitutional amendment.3

Then, in one of my least favorite but most repeated sentences, Ronald Reagan came around. Once a supporter of abortion rights, Reagan had shifted to supporting Jesse Helms’ HLA, and his nomination in 1980 presented an unprecedented opportunity for anti-abortion organizers to further their cause. Alongside Phyllis Schlafly, anti-feminist icon, and Carl Anderson, an aide to Jesse Helms, Bopp got to working drafting language for the Republican platform. Thanks to their influence, Reagan “pledge[d] the appointment of new justices on the Supreme Court who respect traditional family values and the sanctity of all human life.” The pro-life movement’s attempts to push politicians to nominate pro-life justices had officially begun.4

This strategy, too, suffered (deserved) setbacks. In 1981, Reagan nominated Sandra Day O’Connor to the Court. Establishment conservatives lauded her “impeccable” credentials, but she wasn’t openly anti-abortion, so pro-lifers inundated the White House with calls and letters opposing her confirmation. Still, the Senate unanimously confirmed her appointment. Learning their lesson, the Reagan administration later nominated Judge Robert Bork, who “would not hesitate to overturn constitutional aberrations such as Roe v. Wade,” to fill an opening in 1987. But Dems rallied against Bork and shot down his confirmation.5

Eager to avoid further brouhaha, Reagan and his successor, George H.W. Bush, appointed uncontroversial justices Anthony Kennedy and David Souter, neither of whom openly opposed Roe v. Wade. And indeed, in 1992, they upheld it in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. Souter, Kennedy, and O’Connor joined the Court’s then-liberal minority in siding with Planned Parenthood and wrote that “the ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.”6

This refreshingly reasonable take mirrored the public’s continued support for abortion protections, but not James Bopp’s. From his perspective, Republican presidents were too eager to nominate consensus nominees who could sail through Congress. To have more say in Supreme Court nominations, he argued, the pro-life movement needed more influence over Republican politicians. And what could give the NRLC more sway?

Money.