Dearest subscriber,

Here we are in 2022 (happy New Year!), and it just so happens that I write to you on January 6th, the one-year anniversary of the Capitol Riot. The only day that I recall with more dread from 2021 is SantaCon.

Today, I’d like to build on some history we’ve explored before. Last year, we dug into the Greensboro Massacre of 1979, when neo-Nazis and white supremacists came together to attack members of North Carolina’s Communist Workers Party. This event cemented a union between the hate groups and gave rise to the white power movement as we know it today. In another episode of the web series, we traveled to Nicaragua, where the US employed white supremacist mercenaries to fight the Sandinistas, a people’s movement consisting of socialists and left-wing Christians whom the mercenaries viewed as threats to the US.

Notably, in each of these events white power activists, many of whom were Vietnam veterans, acted in the name of protecting the US from communism. And yet, last year white power groups—their ranks still swelled by veterans—attacked the Capitol, a symbol of the US state itself. The white power movement’s goal was no longer to support the US government but to overthrow it, a seismic change. So, when and why did the movement’s aims transform, and what does the persistent presence of veterans in far-right acts of extremism tell us about limiting almost-as-bad-as-SantaCon days in the future?

To answer that question, let’s talk about shrimp.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, shrimp populations in the Texas Gulf were in decline. Decades of unregulated behavior by oil companies had taken their toll on the Gulf ecosystem, and once-reliable catches of shrimp and crab were becoming increasingly scarce. Add in the stagflation of the 70s—a combination of rising inflation, slow economic growth, and growing unemployment—and it was an anxious time to be a Texas fisherman.

And yet some fishermen were still able to eke out a reliable living: specifically, Vietnamese refugees. Displaced by the Vietnam War and resettled by the US government in Texas, many Vietnamese refugees made their way to the coast. Building on experience shrimping and crabbing in similar bays in Vietnam, they worked twelve-hour days regardless of the weather and frequently netted larger catches than their white counterparts. As one white fisherman complained, “They ain’t beating us with brains… they’re beating us with a lifestyle. They live eight or ten to a trailer and eat only what they catch. How do you compete with that?”1

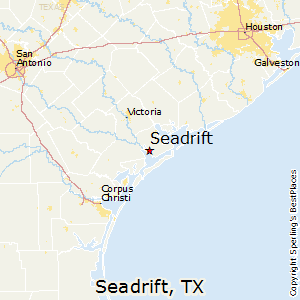

Clearly, the big-brained white fishermen weren’t so pleased about the influx of Vietnamese competition. This was particularly the case in a small town called Seadrift, where by the late 1970s, 10% of the population consisted of Vietnamese refugees.

Tensions between the two sides mounted. In August, a fight ended in the shooting of a white crabber. The following year, three Vietnamese boats were firebombed, two Vietnamese shrimpers were beaten, and another was shot in the leg when walking across a dock without permission.

Of course, there was more than just economic anxiety at play. Many of the white fishermen were Vietnam vets who felt the US government was doing more to help the refugees than soldiers. “Uncle Sam has broken his promise to the Vietnam veterans and kept his promise to the Vietnamese,” said Gene Fisher, a veteran and Seabrook shrimper.2

Racism also informed Fisher’s view. Zooming out for a sec, the US military has long served as a fertile breeding ground for racial hostility. Dating back to 1898 writes historian Greg Grandin, enlisting has provided prejudiced soldiers the chance to “fight in the name of the loftiest ideals—liberty, valor, self-sacrifice, camaraderie—while [still] putting down people of color.”3 These unaddressed, festering white supremacist sympathies were on full display in Seadrift, where white fishermen accused the refugees of being members of the Viet Cong. Little could be further from the truth: many of the Vietnamese fishermen had served in the South Vietnamese military, i.e. as US allies during the war.

Then, to make this mixture of aggression and bigotry even worse, a guy named Louis Beam got involved.