Good morning, subscriber,

And welcome to the tail end of another tranquil week, which I feel like I can say because I’ve been staring unblinkingly at a neighbor’s fish tank for 120 consecutive hours to dull the pain—that is, with the exception of taking breaks to write to you! I hope that your blood pressure has remained somewhat stable over the past couple of weeks and that anyone you know affected by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is alright.

I have a few reactions to the hostilities, although I should note that I’m not so well-schooled on Eastern European affairs, nor on military strategy, nor on whatever is swimming through Vladamir Putin’s mind (unless, like me, it’s a bunch of goldfish). And maybe it’s not so wise to draw historical parallels to a situation that is evolving head-spinningly fast. However, I still have a couple of thoughts informed by the Cold War.

First, history shows that if US officials are denouncing Russian military aggression, they’re probably also quietly conducting their own warfare. This was the case in the 60s when the JFK administration blasted the Soviets for initiating the Cuban missile crisis while secretly fomenting unrest in Indonesia and instigating a 30-year-long civil war in Guatemala. It was also the case in the 80s when during the Soviet-Afghan War, Reaganites secretly sold missiles to Iran to fund a war in Nicaragua. And surprise, surprise, it’s also the case today. Just as the crisis in Ukraine tipped toward invasion, and right around the time Vladimir Putin employed "the unconcealed language of imperialism and colonialism" to justify his aggression, the US bombed Somalia. Per author Spencer Ackerman, this was the fifth US drone strike in Somalia of Biden’s presidency, and it comes on the heels of recent revelations that a botched US drone strike in Afghanistan last year killed 10 innocent people, including seven children.

On the surface, Somalia and Afghanistan don’t have a whole lot to do with Ukraine, but as Ackerman points out, “You do not, in fact, have to choose between American and Russian imperialisms. The correct choice is to detest and resist both.” Amen.

Second, I’m increasingly flabbergasted that the war got to this egregious point. Again, I’m no expert, but it sure seems like the conflict could’ve been avoided. There was opportunity after opportunity for western officials to negotiate with Putin on his most significant demand: a legal, written pledge that neighboring Ukraine and Georgia wouldn’t join NATO. For the record, it’s not just Putin who wants this assurance. For reasons outlined here, hostility toward NATO expansion “is almost universally felt across the domestic political spectrum” in Russia, including by Putin’s sharpest liberal critics.

And yet US and British officials repeatedly refused to budge on this demand. What gives? Well, yes, I know they’re not keen to negotiate with a warmonger who deserves to spend the rest of his days floating in the shark tank at the aquarium. However, I’d also argue that the unnecessarily hardline mentality toward the USSR that developed in the 1950s is still around today. Indeed, as evidenced by the actions of the Eisenhower administration leading up to the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, US leaders have long talked a big talk about the Kremlin, to the detriment of the Europeans who actually end up fighting it.

To see what I mean, let’s first talk about Stalin.

In 1953, the brutal, brutal dictator finally met his demise after thirty years in power. Various political factions vied to define the USSR’s future, and Nikita Krushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party, ended up leading the charge. His goal? The de-Stalinization of the Eastern Bloc, i.e. permitting the liberalizing of politics in Soviet satellite countries and the ascendance of reformist Communist politicians who were a little less into ruling with an iron fist than Stalin and his acolytes had been.

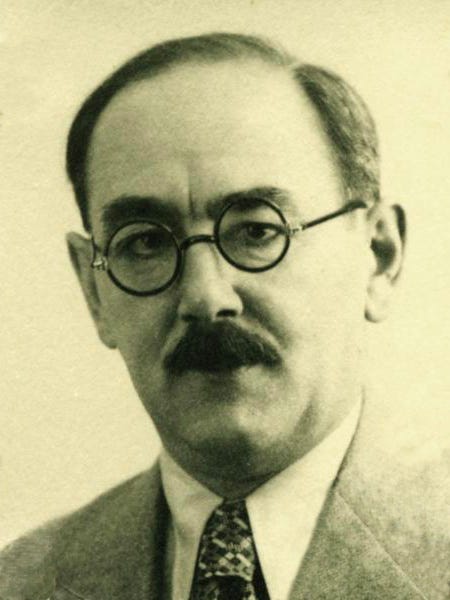

A telling example was Imre Nagy, who became de facto prime minister of Hungary shortly after Stalin’s death in 1953. Nagy favored “socialist legality,” which in plain language meant less repression, a more humane political order, and the rise of one or two new political parties to check the Communist Party’s dominant position in Hungarian politics. In other words, his aim was to chart a middle path wherein he obtained limited pluralism at home in exchange for supporting Soviet foreign policy abroad. In turn, these policies might put Hungary on the slow but steady path to break free of the Kremlin’s influence.1

Alas, in the US during the 50s, the phrases “slow and steady” and “middle path” were about as popular as “maybe don’t add olives to the Jell-O.”

Recall that the 50s represented the peak of the influence of our old pals, the Dulles Brothers. Secretary of State and Director of the CIA under President Dwight Eisenhower, Dull and Duller held a black and white view of the world, in which there was no room to distinguish between Stalinist and reformist communists.2 You were either a capitalist or a communist, and that was that. Add in the fear that Senator Joe McCarthy generated, and “rational discourse in the US government about communism and how to deal with it” was “all but stifled,” writes Charles Gati.3