Welcome to the end of another week, subscriber!

And a belated happy Valentine’s Day. Although a few days have passed since the lovely holiday, I assure you, you’ve been on my mind and in my heart all week. Your presence was a welcome balm to the sadness and fury I felt after reading a report by the Washington Post about fatal police shootings in 2021.

Despite the historic demonstrations in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd and the widespread calls for police reform that followed, the police shot and killed 1,055 people nationwide last year, the highest total since the Post began tracking this data. The new count is up from 1021 shootings in 2020 and 999 in 2019, even though more than 400 bills were introduced in state legislatures last year to address officers’ use of force.

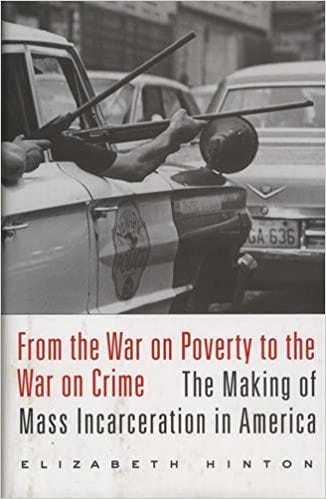

This disturbing uptick shouldn’t come as a surprise. The federal government has invested heavily in arming local law enforcement since anti-police demonstrations in the 1960s. President Biden maintains this support today. And though he’s also passed legislation targeting the structural inequality that often leads to violent confrontations with law enforcement, LBJ’s attempt to walk the same tightrope reveals it’s kinda hard to have it both ways.

To see what I mean, let’s head back to the Watts neighborhood of South Central LA in 1965.

In the decades after World War II, unemployment in Black urban neighborhoods skyrocketed. As major corporations like GM, Chrysler, and Firestone shifted toward relying on suburban and overseas labor, they closed factories largely staffed by Black civilians who’d moved to northern cities following the rise of Jim Crow in the South. Consequently, while unemployment nationwide hovered around 5% in the 1960s, in predominantly Black communities like Watts, as many as one in three people couldn’t find work.

Nor could they find the training to qualify for new work. LA was deeply segregated, and the underfunding of Black neighborhoods meant schools lacked the resources to prepare students for careers in growing industries like aerospace, engineering, and dead sexy international espionage (assuming Austin Powers is a documentary). Add pervasive over-policing of communities of color to this backdrop of mass unemployment, extreme segregation, and poverty, and you could say things grew a little heated in places like Watts.

In the summer of 1965, tensions reached a boiling point. On the evening of August 11th, a few hundred locals witnessed the beating and arrest of Rena Price and her 21- and 22-year-old sons by a group of California Highway Patrolmen and the LAPD.

Residents responded by hurling cement, rocks, and bottles at the officers. Community leaders pleaded with the police not to escalate the situation they’d instigated, but the following day, the LAPD paraded six cars down 118th Street in Watts, where 500 protestors had gathered. “It was just like an explosion,” one witness later said of the scene; “everything just went haywire.”

Over the next four days, Watts residents took to the streets and destroyed $200 million in property. Meanwhile, Governor Edmund F. “Pat” Brown doubled down on state aggression and called out the National Guard for the second time in California’s history, bolstering an “attacking force” of 16,000 policemen led by police chief William Parker. Parker treated the uprising as an insurgency that, in his words, was “very much like fighting the Viet Cong.” When all was said and done, 31 Watts residents died at the hands of law enforcement, while a fireman, a deputy sheriff, and a policeman also lost their lives.

The violence mirrored rebellions in 250 other cities during LBJ’s presidency—eventually, a few hundred years of structural issues tends to frustrate people. To his credit, LBJ’s initial inclination was to address persistent inequality. In 1964, he launched the War on Poverty, which included programs like Job Corps and Head Start, meant to provide additional job training and educational opportunities in lower-income areas, respectively. Just a week before the Watts Rebellion, LBJ also signed the Voting Rights Act, one of the most wide-sweeping pieces of federal civil rights legislation in US history.

But in many ways, the Watts Rebellion pushed LBJ and his administration in a new direction. Sensationalized depictions of the uprising appeared in publications like the Wall Street Journal and the Times, blaming the violence on Watts residents.

These portrayals, along with growing conservative criticism of civil rights gains, led LBJ to declare that “effective law enforcement and social justice must be pursued together.” So, a month after the Watts Rebellion, in September 1965, he signed the Law Enforcement Assistance Act, marking the official start of a war on crime to complement the War on Poverty. To initiate the War on Crime, he formed a Crime Commission to devise “daring and creative and revolutionary” policy suggestions.