The Inventor of Anti-Racist Geopolitics

And the erasure of Black scholarship, with Professor Barbara D. Savage

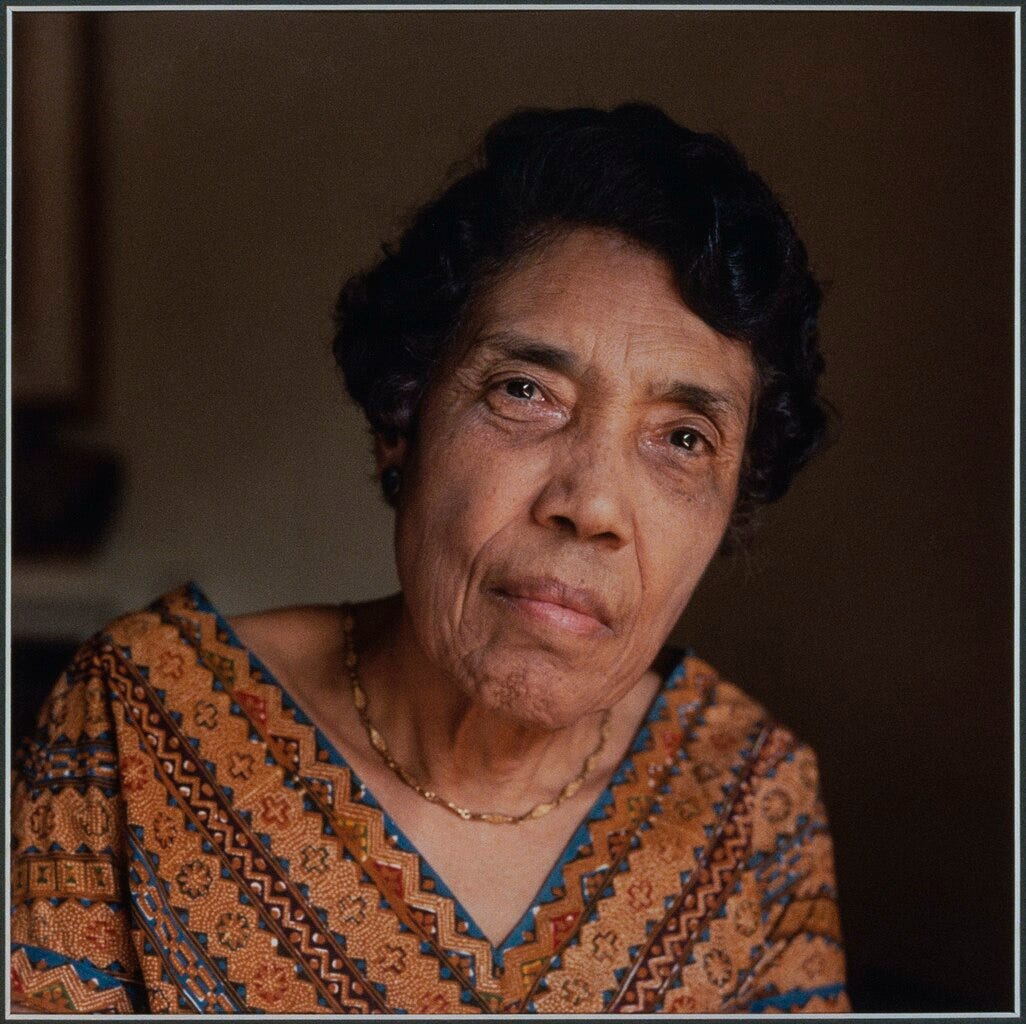

In Merze Tate: The Global Odyssey of a Black Woman Scholar, and in conversation, Professor Barbara D. Savage (University of Pennsylvania) resurrects the vibrant life of Merze Tate, “the highest achieving Black female intellectual ever to be forgotten by the history books.” We explored Tate’s work, often ahead of its time, and what the erosion of her legacy suggests about the erasure of Black scholarship as a whole.

A condensed transcript edited for clarity is below. You can also listen to the audio of our conversation, which includes more on the development of Tate’s theories, her various other interests (including inventing ice cream machines), Professor Savage and I discussing playing bridge together, and more:

The Inventor of Anti-Racist Geopolitics

Listen now (31 mins) | Audio of my conversation with Professor Savage.

Ben: Professor Savage, to begin, I wonder if you could talk about Merze Tate’s connection to Michigan and how in her early years, her intellectual ambition was already vividly on display.

BDS: Tate was born in the middle of Michigan in 1905. Her parents and her grandparents had migrated there to take advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862. So she came from people who took a great deal of pride in their independence and their entrepreneurship, which really shaped her.

By the time she was 16, she was participating in debate contests, speaking on topics like the mistreatment of Black soldiers during World War I. Later, in 1927, she graduated from the University of Western Michigan as the top student. She trained to be a high school history teacher but ran smack into racial restrictions in her home state and had to leave to get a job.

Ben: I noted that in one job interview in St. Louis, she was nervous when the white superintendent gave her a surprise history exam — but once she heard the questions, she realized that “I probably knew more than the school board members.”

BDS: Yes. She had a tremendous amount of ego strength, which is not to say that she lacked humility, but from a very, very young age, she felt extremely competent about her abilities.

Ben: Another representation of her confidence was traveling by herself — a lot. Tate seems like the most well-traveled person you can imagine.

Her travels picked up after she got her first teaching job in Indianapolis. How was her time there transformative in her journey to becoming “a world traveler, a scholar, and a cosmopolitan woman”?

BDS: The job brought her into a particularly rich Black urban space, different from what she had lived in before.

The thing that really made her career and travels possible was that she was asked to join the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, a Black women's sorority (Vice President Harris is actually a member). They had organized and raised money for an international fellowship so that Black women would be able to go and study for a year abroad.

Tate was the third woman to hold that fellowship. She had the extremely unlikely goal of using it to get a graduate degree from Oxford — which she then did, becoming the first black American to receive a graduate degree from there (in international relations).

While in Oxford for three years, she traveled widely across the U.K., Europe, and beyond.

Ben: Later, she earned one of the first Fulbright scholarships, which she used to spend a year in India. How did her Fulbright year push her to study race, slavery, and imperialism in the Pacific — a region to that point not so explored?

BDS: Before she left for India in 1950, she conceptualized an enormous trans-imperial project. She wanted to see the colonizing impact of European countries, as well as the United States.

That’s partly why she was trying to get to Asia and the Pacific. Of course, when in India, she traveled widely by train and little airplanes. India had just shaken British rule. She witnessed both the continuing presence of the Raj, but also the struggle of the Indian people to reclaim financial independence.

Moving around the region, she began to think more deeply about the consequences of imperialism. After she came back to the States, she decided to focus squarely on interventions in Hawaii, which she traced back to the 1820s.

Much later, toward the end of her career, she studied Africa. Tate saw that even in post-independence African nations, the involvement of international corporations in building railroads and seaports and mineral extraction was as big of a threat to their economies and people as if nation-states were showing up on the shores.

Ben: You write, “Links between race, imperialism, and technology would be central” to one of “her most important theoretical innovations”: anti-racist geopolitics.

Meanwhile, she came up with her theories and analyses amid a time when Black scholars had a lot of trouble breaking into any field, let alone Black women scholars.