Good morning, subscribers of the universe,

Last week, we looked at a racist textbook used in Mississippi until the 1980s. Today, we dive into why that textbook existed in the first place:

This week’s story comes from Dixie’s Daughters, by Professor Karen Cox and Race and Reunion, by Professor David Blithe. I also cite a journal article by Professor Sarah Case, an investigation by Greg Huffman, and Teaching Hard History, produced by the SPLC.

Next time on Skipped History…

We’ll explore American History, one of the most used textbooks in, well, American history.

In a Ted Talk on Teaching Hard History, Professor Hasan Kwame Jeffries quotes performer and educator Regie Gibson, who said, “Our problem as Americans is we actually hate history. What we love is nostalgia.”

Mildred and next week’s protagonist, David Muzzey, would have to agree. And BTW, Hasan’s whole talk is worth a listen, not least because he’s from Crown Heights.

The transcript of today’s video is below. We’re off next Thursday, so (I can’t believe I’m saying this) see you after the election! In the name of the heavenly election mother, may every attempt at voter suppression backfire, amen.

Ben

Can’t wait for two weeks? Follow Skipped History on Twitter for more bits of skipped history.

This week’s transcript

Hello, my name is Ben Tumin, and welcome to Skipped History. Today’s story is about an early 1900s “historian” named Mildred Rutherford. I read about her in Dixie’s Daughters, by Professor Karen Cox, and Race and Reunion, by David Blithe.

Mildred, Mildred, Mildred, where to begin? Oh, fashion. For nearly half a century, beginning in 1876, Mildred taught history at the Lucy Cobb, a girls’ school in Athens, Georgia. She also served as principal, and, in an effort to cultivate moral southern “ladies,” she prohibited students from talking to boys, wearing makeup, or receiving gifts other than fruit. Before group outings, Mildred would also measure each student’s skirt to make sure that it fell below the ankle because, a banana: How could that spur a young imagination? But an Achilles tendon…

This is the key to understanding Mildred: the main thing that mattered to her was restoring the hierarchy that had existed before the Civil War. In her defense, the war was traumatic. Her mother, Laura, tended to wounded Confederate soldiers at the family home, so young Mildred saw a lot of gory stuff. The war also wiped out her family’s wealth, which until then had led to a nice childhood. You know who probably didn’t mind the war as much? The 209 people enslaved on her grandfather’s plantation, but based on her experience, Mildred developed a longing for the days of the pre-war past.

That’s why she wanted her students to be proper, deferential ladies, and why she promoted a mythology called the Lost Cause. A term that first appeared in The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates, an 1866 book by author Edward Pollard of Virginia, the Lost Cause became a historical narrative that minimized slavery’s role in the Civil War and presented white people as the war’s real victims. In the early 1900s, Confederate heritage groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which Mildred belonged to, began a concerted effort to spread the Lost Cause. One way they did that was by erecting monuments to Confederates who’d forgotten to iron their jeans on statue day. Another approach, which Mildred championed, was to write the Lost Cause into textbooks.

Her big moment came at a 1919 conference among confederate heritage groups, which you can picture like a MAGA rally but with cooler hats. There, Mildred published “A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books, and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries.” In her pamphlet, she called for schools to reject a textbook “that says the South fought to hold her slaves”or that “speaks of the slaveholder of the South as cruel and unjust” because, on the contrary, “the servants were very happy in their life upon the old plantation… They are treated with such great humanity and kindness… How they sang! How they danced!... So free, so happy!” Now, you know it’s bad when you have to put the word “so” in front of the word “free”—that’s kinda like my real estate agent saying this building is so up to code or Heidi Cruz saying her husband Ted is so not the Zodiac killer, but Rutherford was undeterred.

In 1920, she published “The Truths of History,” which expanded on “A Measuring Rod” and maintained that the South seceded not because it wanted slavery, but because the “Tariff Acts of 1828 and 1833 were unconstitutional.” In “The Truths of History,” Mildred also called out offending textbooks by name, like David Muzzey’s “An American History,” published in 1911, which said the South did fight for slavery and was one of the most used textbooks in northern states. In southern states, “Truths of History” became a blacklist for textbooks.

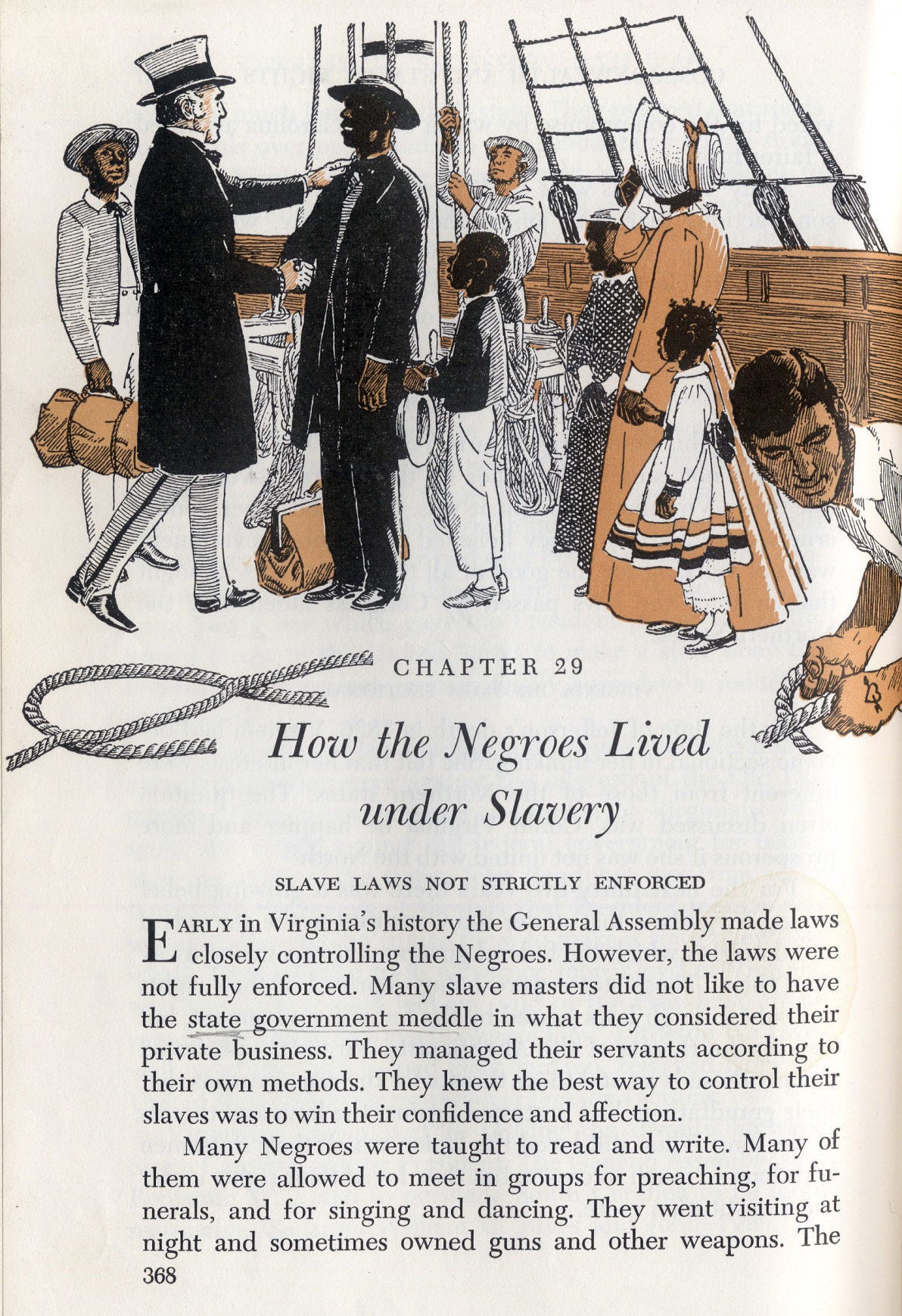

Over the ensuing decades, statewide textbook boards like the one we saw in Mississippi last week began popping up. Texas’ formed in 1920; Mississippi’s in 1940; Virginia’s in 1950, and so on. The goal of the commissions was clear: to concentrate power over how history was taught in a small group of hands. Totally by coincidence, the textbook commissions were often staffed by members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and later, by segregationists. That’s why a Lost Cause book like Your Mississippi was in use until 1980, and why, in just one of many other examples, a 7th grade Virginia textbook in use from the 50s through the 70s said that enslaved people were allowed to meet “for singing and dancing… most of them were treated with kindness.”

That is Lost Cause mythology and Mildred Rutherford’s language repeated almost verbatim. According to one researcher, 70 million students, if not more, may have read similar material. Fast forward to a poll conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center of 1,000 high school seniors in 2018, and they found that “only 8% of high school seniors can identify slavery as the cause of the Civil War. Almost half of the respondents (48%) said tax protests were the cause.” And to top it off, almost all of the respondents said that young ladies should only receive Edible Arrangements as gifts, which I find unfair because I enjoy them myself.

My point is, Mildred’s version of history is alive and well, which leaves me with a question: if generations of students learned the Lost Cause in the South, what actual truths of history did it obscure, and what were kids reading in the North?

Well, as we’ll see, Mildred’s contempt for David Mizzey’s American History, the textbook in the North, may have been justified. Tune in next time to learn more about that bit of skipped history.

That’s all for this week. Thanks for watching Skipped History! To share this article as a web page, click the button below:

If you’d like to post a comment, click the “Leave a comment” button:

And for more bits of Skipped History, check out SH on Twitter.

Take a deep breath, look at some trees, and see you again when we have a new president.