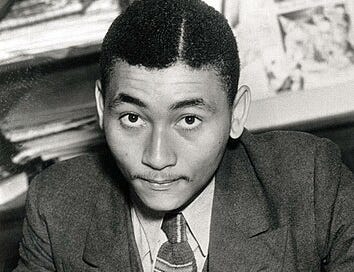

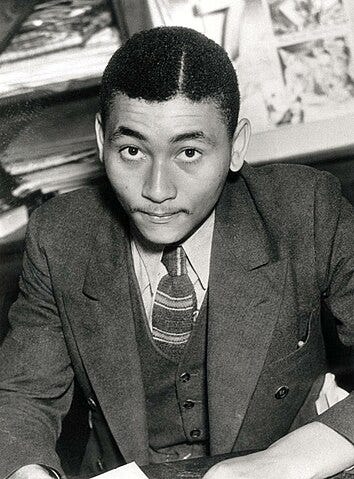

My guest today is Professor Brad Snyder, author of You Can't Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads: Angelo Herndon's Fight for Free Speech. Herndon was a Black Communist Party organizer who found himself at the center of a landmark court case in the 1930s. The case made him one of the most famous people in the country, and generations of protesters have “stood on his shoulders.” Yet today, he's often forgotten. Professor Snyder helped me bring his legacy back to life.

Professor Snyder teaches constitutional law and 20th-century American legal history at Georgetown. He’s written for Politico, Slate, and The Washington Post and has made numerous radio and TV appearances. A condensed transcript, edited for clarity, is below. You can also listen to our conversation on the Skipped History podcast:

The 18-Year-Old Who Won Us the Right to Protest

Listen now (~40 mins) | Podcast version of my conversation with Professor Snyder

Ben: To begin, can you give us a little background on Angelo Herndon? Who was he? Where was he from? And why did he hide his identity?

BS: Well, Angelo Herndon was an 18-year-old Black communist who was sent by the Communist Party to Atlanta, Georgia, to organize Black and white unemployed workers at the height of the Great Depression in 1932. His identity was hidden—most Communist Party figures changed their names to protect their families.

Herndon was from a family of sharecroppers in rural Alabama and had actually started with the Communist Party in Birmingham, Alabama. His real name was Eugene Angelo Braxton.

Ben: The steps he took to cover up his identity made me think of The Americans.

BS: I think Herndon was in a similar amount of danger as the spies in that show, if not more.

Georgia was an apartheid state. Black people were ruled by white supremacists who dominated the Democratic Party. White supremacists also terrorized communists, and the U.S. government was going around the South holding hearings about Communist Party infiltration. So to be both Black and communist in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1932 was a scary thing.

The threat of imprisonment, the threat of violence—Herndon lived with them constantly. If anything, when he was arrested in 1932, Herndon should have been more on guard.

Ben: What led to his arrest?

BS: Budgets were strapped in the Great Depression. Fulton County, where Atlanta is, decided to cut off all unemployment relief.

Herndon arranged a peaceful protest of county officials’ decision in front of the Fulton County courthouse. It was a protest with unemployed Black and white workers. They were marching with placards, talking with police officers on the scene. No one was arrested. Three days later, county officials reversed their decision and restored all unemployment relief—and then some. The Communist Party declared victory.

I think county officials were really sore at the leader of the protest—Herndon, who was all of 18 years old—and annoyed that the Communist Party was gaining a foothold. And the very idea of an interracial protest in segregated Atlanta was a threat to the white political establishment.

Shortly after the reversal on unemployment relief, Herndon went to the post office to pick up the Communist Party’s mail. Two police officers were lying in wait. They arrested Herndon, seized all the communist literature under his arm, forced their way into his rented room without a search warrant, took all his radical literature, and threw him in jail. He was held incommunicado for 12 days.

Ben: Can you talk about the tortured justification for imprisoning him?

BS: County officials charged him, under an old Georgia slave insurrection statute, with attempting to incite an insurrection—a capital crime, punishable by death, with a minimum penalty of 18 to 20 years on a chain gang. It was a really controversial charge, and it set in motion a series of events that made Angelo Herndon one of the most recognizable Black figures, not just in the U.S., but all over the world.

Black and white people, Republicans and Democrats, rich and poor—all rallied to Herndon’s cause. A young Black Harvard-educated lawyer, Benjamin Davis Jr., defended Herndon at trial for free. A young Georgia Tech English instructor, C. Vann Woodward, who later became one of America's leading historians of the South, joined the interracial committee to free Herndon. A radical New York lawyer, Carol Weiss King, essentially the Communist Party’s lawyer, led the appeals process and assembled a legal dream team.

Ben: She comes off as such a badass in this book.

BS: Totally. She fought against the deportation of radicals and immigrants—a lot of resonance today.

And remember what 1932 was like. You had a rising tide of fascism all over the world. Hitler was on the rise in Germany. Mussolini was on the rise in Italy. People were worried and saw free speech and peaceable assembly as essential to what makes America a democracy.

So I think that's what drew such a diverse group to Herndon’s case. In July 1933, he was convicted by an all-white jury in Georgia for attempting to incite insurrection and sentenced to 18 to 20 years on the chain gang—simply because of the reading material in his possession. People were like, what's going on here? This sounds like the book burning that's going on in Germany.

Herndon's crack legal team appealed the case to the Supreme Court. If you're going to charge somebody with inciting insurrection, they said precedent held that you need an imminent threat of violence—emphasis on the word imminent.

Ben: In their words, Herndon might as well have been charged for carrying “a copy of the Encyclopedia Britannica."

I picture volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica high-fiving each other after hearing they came up. It might be the most exciting reference to the Encyclopædia Britannica in world history.

BS: Ha, well, Ben, another thing to note is there were not a lot of cases before 1925 where the Supreme Court said, Hey, this conviction violates the First Amendment. Also then, like now, the Court had a conservative majority, which was striking down Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. So, on the surface, things didn’t look great.

But Angelo Herndon didn’t become one of the most famous Black people in America and around the world by accident. Eleanor Roosevelt knew about Herndon’s case. Herndon even had a face-to-face meeting with FDR. There was a groundswell of support. When Herndon was released from prison—twice on bail—he was literally carried on the shoulders of people out of New York’s old Penn Station onto the street.

Ben: Only in part because being carried on shoulders was one of the fastest methods of travel from the old Penn Station.

BS: Ha, good point. At one point, Herndon gave a speech before 4,000 people in Harlem. Speaking about the Southern ruling class, he said, "They can send me to the electric chair. They can wreck my body, but they cannot break my spirit for the working-class struggle. It is not a question of unemployment relief, but it is a question of life and death, a question of political power."

Ben: So how did the case shake out? You note it hinged on a lesser-known justice.

BS: Yes, Justice Owen J. Roberts.

Roberts was part of the conservative majority. He’s what today we would call a swing vote. And unlike many other scholars, I argue that he had a profound sense of justice. Later, he was one of three justices who dissented in the infamous Korematsu case, where the Court upheld the internment of Japanese Americans. In dissent, Roberts said the Japanese internment camps were concentration camps.

In Herndon’s case, the decision itself was somewhat narrow. Roberts didn’t strike down the Georgia insurrection law itself, but he wrote, “The power of a state to abridge freedom of speech and of assembly is the exception rather than the rule.” He protected the rights to free speech and peaceable assembly and saved Herndon from the chain gang.

Ben: Ever since, you write, “Generations of protesters, from civil rights activists to white supremacists, stand on the shoulders of Angelo Herndon.”

BS: Yes, for a long time, on all parts of the political spectrum, we've taken our ability to march in the streets for granted. But in many ways, it traces to Herndon, Roberts, and this case.

Afterward, Herndon did a great job capitalizing on his fame. He wrote an autobiography, Let Me Live, which received rave reviews. After that, he was an accomplished speaker, traveled all over the country, and wrote for the Communist Daily Worker covering Harlem—one of the few Black reporters at a daily newspaper in New York City at the time.

Later, he started a publication called The Negro Quarterly, which focused on Black literature, art, culture, and politics, and published writings from some of the most accomplished authors in the country—people like Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes.

But ultimately, Herndon left the city and faded into obscurity. The FBI tracked him for decades because of his ties to the Communist Party, but even they lost sight of him by 1971.

Ben: That reminds me of James Baldwin’s quote from 1961: "I remembered Angelo Herndon and wondered again whatever had become of him."

BS: That was one of the big reasons I wanted to write the book: to answer the question, “What happened to Angelo Herndon?” He’s a central figure of civil rights history—a reminder that our right to protest was won (and can be taken away).

For decades, Herndon was one of the most famous people in the country. If anyone wants proof, they can go into the new Moynihan Train Hall in New York City and see a mural depicting the incredible scene of New Yorkers welcoming him in 1934.