Explaining the Obsession with the Panama Canal

With Professor Julie Greene

To say there’s a lot going on right now is an understatement. One area where I can offer some clarity, thanks to Professor Julie Greene, is Panama.

Professor Greene, a labor and migration historian at the University of Maryland, is the author of The Canal Builders, nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 2009, and most recently, Box 25: Archival Secrets, Caribbean Workers, and the Panama Canal. She details the experiences of the people who built the Panama Canal. She also explores how American officials, despite enforcing a system of racial segregation and exploitation, draped the project in triumphant imagery. “More than any other project in U.S. history,” Professor Greene told me, “the canal symbolized American beneficence, a selfless gift to world civilization.” That perception still shapes how the canal is remembered today.

A condensed transcript of our conversation, edited for clarity, is below. You can also listen to the podcast version, where we geek out on how the canal works and discuss the lives of its builders at more length:

Explaining the Obsession with the Panama Canal

Listen now (41 mins) | Podcast version of my conversation with Professor Greene

Ben: Can you talk about the beginning of U.S. power on the isthmus, please?

JG: Absolutely. As Theodore Roosevelt took the presidency in the early 20th century, he was eager to build the canal. He saw it as the key to launching U.S. power beyond the North American continent.

There had been dreams of the Panama Canal going back centuries. The problem was that Panama was a province of Colombia at that time. The U.S. tried to negotiate the right to build the canal, and the Colombian Senate rejected it unanimously. They saw it as an attack on their sovereignty and didn’t think the U.S. was offering them enough. So Theodore Roosevelt had to come up with other plans.

He thought about seizing the territory and making it part of the U.S., but ultimately, he decided to encourage a group of Panamanians who wanted to revolt and create an independent country. They did so. They revolted. The U.S. sent a warship to support their efforts.

Here’s the interesting part: in 1903, the Roosevelt administration then negotiated a treaty—not with any Panamanian, but with a Frenchman who had led a private company trying to dig the canal. That treaty gave the U.S. permanent and complete control over the vast region that became the Canal Zone, cutting through the heart of the new country of Panama. It was said that the first president of the Republic of Panama nearly fainted when he learned what had been given away to the U.S.—

Ben: —which included the right to intervene militarily to restore public order, if I’m not mistaken?

JG: And to take more territory if the U.S. deemed it necessary. It was a pretty brutal, naked, imperialistic seizure of the heart of the new republic. The New York Times called it a national disgrace.

Ben: The treaty sounds like a negotiation between an imperialist, like Teddy Roosevelt, and a genie. My third wish is not for more wishes, but for more land whenever I want!

JG: Yes, you could think of it that way.

Ben: The French had attempted construction of the canal but didn’t do such a great job. You talk about how their failure gave Americans an opportunity to project a more positive image. Can you elaborate on that?

JG: Sure. The U.S. began to publicize the canal project as a perfect symbol of U.S. global power, one that rested not on the imperialistic acquisition of the Canal Zone but rather on U.S. scientific, medical, and technological know-how. The idea was that we were going to succeed where the old European powers had completely failed.

The French had tried to build the canal in the 1880s. They failed so disastrously that it nearly brought down the French government, and the leaders of the project nearly ended up in prison. They were terribly affected by diseases—malaria, yellow fever. The top elites used to bring their caskets with them to the canal because they knew they might die there.

Ben: BYOC.

JG: Ha, yes. So the U.S. had a good foil there: look how terrible the French government was, and we’re going to do this right. That said, when the U.S. started the work in Panama, they too found it very difficult. Theodore Roosevelt launched a massive publicity campaign to redeem the canal project.

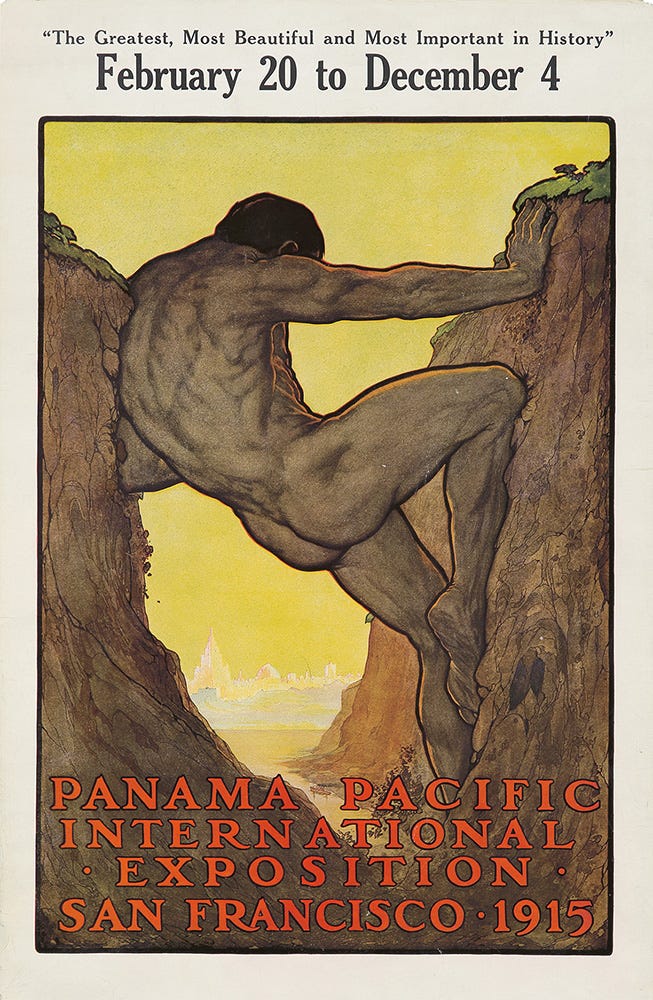

Ben: I noted some of the ways that Teddy Roosevelt and other American officials cloaked the effort in triumphant imagery, including a famous poster for the 1915 World’s Fair, which depicted the U.S. in Panama as Hercules completing his 13th labor.

I looked up that poster, and I will say it’s a little risqué. It seems like Hercules has a very intimate relationship with the mountainside...

JG: Ha, yeah...

Ben: One of the chief engineers was named George Washington Goethals. How did he rule and preserve order in the Canal Zone? And spoiler, how was it not necessarily the most novel means of dividing a society?

JG: Great question. The U.S. created in the Canal Zone a very sophisticated, complex society, but also a really authoritarian one. The U.S. had the power to deport anyone who was not working productively and to sentence workers to prison labor. Through spies and a large police force, the U.S. surveilled workers at every step it could manage.

A key problem for Goethals was labor—namely, where to get it from. Ultimately, they got most of their labor from the British Caribbean, like Jamaica and Barbados—workers of African descent often living at the edges of starvation as landless agricultural workers under British colonialism.

At the beginning, especially, they were unskilled workers—the diggers and dynamiters. There were many other workers too—thousands of U.S. workers, most of them white, working as machinists, foremen, and engineers. There were also thousands of Europeans—some Northern Europeans, but then the U.S. started recruiting Italians and Spaniards, thinking they would push the Afro-Caribbeans to work harder.

To manage this complex labor force, the U.S. used a rigid system of racial segregation known as the silver and gold payrolls. White Americans were on the gold payroll, paid in gold. Their lives were nicer—better paid, better conditions than they would have confronted in the U.S. The silver workers, on the other hand—the Afro-Caribbeans on the silver roll—lived in shacks with no screens on the windows and were fed out of troughs with no place to sit.

Ben: One carpenter you cite, John Butcher, described dinner as a "meal of cooked rice, hard enough to shoot deer... and a slab of meat many men spent an hour trying to chew." So the difference in the system wasn’t just between gold and silver—it was between gold and weapons-grade rice and meat gum.

JG: Ha, there were also differences in work. Afro-Caribbeans had the most dangerous jobs—working where there were premature dynamite explosions, avalanches, railroad accidents. One worker said that when a dynamite explosion happened, "the flesh of men flew in the air like birds that day."

They worked in swampy conditions, digging out avalanches in water up to their waists. They were constantly exposed to malaria. Pretty much every Afro-Caribbean worker dealt with it. And pretty much every one of them suffered an injury of some kind, many of them severe.

But these were complex individuals living through an amazing historical moment. I wanted to write a book that focused on them. When you read their testimonies, on one level, there’s a sense of—my God, we built the Panama Canal! But then they talked about racism; about feeling like the white men were gods and the Black men were dirt.

Ben: You detail how, in the last years of the project, there was a chaotic mass exodus. Instead of the 40,000 people employed at the height of construction, by 1920, when the canal was fully operable, it only needed a few thousand workers to administer and maintain it. Many of those jobs were white-collar or for white American workers.

Can you catch us up on what happened over the next few decades?

JG: The U.S.'s relationship with Panama was always embattled. You can't tear apart a country's sovereignty the way the U.S. did without tensions.

As time wore on, Black Caribbeans in the area were fighting a double war—for civil and labor rights within the Canal Zone and for the same within Panama. At the same time, global dynamics were shifting. By the end of World War II, decolonization was happening around the world. Panamanians started fighting more actively against what they saw as unfair domination by the U.S., which had taken more territory over the years.

A flashpoint came in January 1964. Panamanians had won the right to have their flag flown alongside the U.S. flag at schools, and when they tried to assert that right, white Americans fought back. This conflict escalated. The U.S. military was called in. About a dozen Panamanians were killed, along with four U.S. military personnel.

At that point, U.S. politicians seemed to accept that the canal needed to be transferred to Panama, but U.S. popular opinion still believed it was our canal and we should keep it forever, harkening back to Roosevelt’s publicity campaign. More than any other project in U.S. history, the canal symbolized American beneficence, a selfless gift to world civilization.

Ben: You write that, back in the early 1900s, “Articulating the Panama Canal as an exceptionally American project... required generating silences, which continue to shape the historical narrative around the canal today.”

JG: Yes. People never could understand—and some still don’t today—that Panama sacrificed a huge amount. The canal wasn’t just a selfless gift from the U.S.; it was an imperialistic seizure of someone’s sovereignty.

In the 1970s, Reagan found that when he mentioned the Panama Canal, there was huge popular opposition to transferring it. He used that reaction to strengthen his bid for the presidency. Meanwhile, in 1977, President Carter negotiated the treaties with Panama that led to the final transfer of the canal in 1999.

Ben: Talk about a slow burn...

What do you think about Trump’s stated wish to regain control of the canal? How does that feed into this history and the experiences of the people you chronicle in the book?

JG: You know, to Panamanians, I think Trump’s statements are shocking. They’ve been running the canal for a quarter-century, and they’re doing it better than the U.S. did—more efficiently, making more money, and operating more safely. They even taxed themselves to expand the canal, which was a spectacular undertaking. The canal is a major part of their economy and national pride.

The U.S. whitewashes the brutality its government has been involved in around the world. There’s no better example than how we talk about the Panama Canal. It’s framed as heroic while erasing both Panama’s role in supporting the project and the labor exploitation and racial segregation that made it possible.

Thanks for your help.

I am trying to reach someone in the admin of Substack. A colleague who has posted here has died suddenly. His family has asked for assistance in preserving his writing. Ben....can you provide contact info to help them?